It's time for customers to solve market problems that businesses can't solve by themselves.

Every node is a peer on the Internet. Let's take advantage of that fact.

The expression “supply and demand” was coined by James Denham-Steuart above) in 1767. But he put demand first, saying demand and supply. Of the two, he wrote, “it must constantly appear reciprocal,” adding, “the nature of demand is to encourage industry.” Nine years later, in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith wrote, “The real and effectual discipline which is exercised over a workman is that of his customers. It is the fear of losing their employment which restrains his frauds and corrects his negligence.”

My point: both these bright bulbs in the Scottish Enlightenment saw customers as equal partners with businesses in creating markets and prosperous economies—and as leaders in dances between demand and supply.

Alas, after industry won the industrial revolution, customers came to be seen (at least by big business and business schools) as mere dependents, with no more agency than what businesses and regulators provided them.

Worse, they became mere “consumers,” which Jerry Michalski calls “gullets with wallets and eyeballs.” In usage, “consumers” outpaced “customers” starting in the 1930s, in the first golden age of broadcasting. Then, when personal computing took off, the industry became the only one other than drugs to call people “users”:

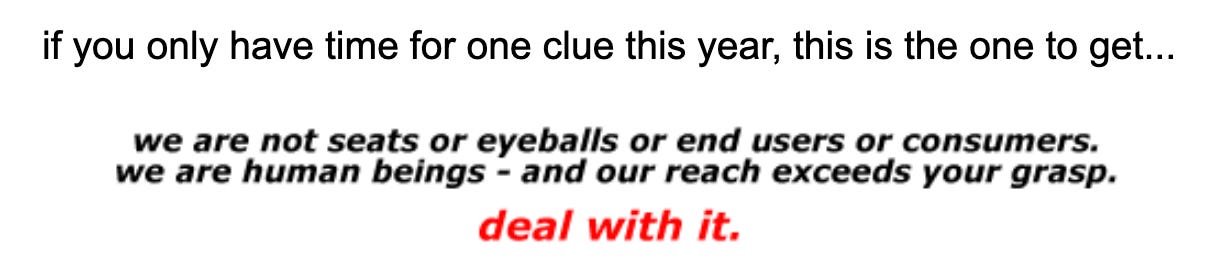

Meanwhile, the Internet by design made peers again of customers and companies. Some of us (such as the four authors of The Cluetrain Manifesto, of which I am one) even thought customers would take the lead in their dances with business:

That year was 1999.

Since then the reach of online businesses—especially those in the tracking-based advertising racket (which includes most online publishing)—has grasped the living shit out of us.

Yes, we get lots of goodies in the process, but business on the whole does not welcome what Smith called customers’ “real and effectual discipline.” Instead, businesses buy “solutions” for scaling care across many customers. These solutions are called CRM (for Customer Relationship Management) and CX (for Customer Experience), and rationalized around “delivering” an “experience” that a “consumer” or a “user” can value and trust.

The problem for customers is that every company doing CRM or CX does it differently, even if they all use the same few back-end software systems, sitting in the same Oracle, Salesforce or SAP cloud. All of them also presume no more agency on the customer’s side than what the company provides. So, at best, all these systems can provide are okay experiences of captivity.

Now think about what will happen when customers are free to operate solutions of their own that scale across all many companies. Like this:

The fulcrum in that graphic—the category of tools that give an independent customer leverage—is VRM, for vendor relationship management. Any tool that gives a customer leverage in its dealings across many businesses is VRM. (The term was coined in 2006, at ProjectVRM, as the customer-side counterpart of CRM, or customer relationship management.)

It helps that we already have some familiar VRM tools. Cash is one. From The Cash Model of Customer Experience:

Here’s the handy thing about cash: it gives customers scale. It does that by working the same way for everybody, everywhere it’s accepted. It’s also anonymous by nature, meaning it carries no personal identifiers. Recording what happens with it is also optional: using it doesn’t require an entry in a ledger. Cash has also been working this way for thousands of years. But we almost never talk about our “experience” with cash, because we don’t need to.

You might think that businesses, especially those with CRM systems, would welcome VRM tools, especially given how hot the buzzphrase know your customer, initialized as KYC, has become:

Look up KYC on Google today and you’ll get over four million results. The problem with KYC is that companies four million companies will use CRM tools to know their customers in four million different ways. And all of them get screwed up when the customer moves or changes some other variable, such as their email address, phone number, credit card, or surname. Fixing that problem for all the databases that know a customer, and doing it in one move, can only be done from the customer side.

Think about the cost savings for all companies of a tool that gives customers a way to change their records with all those companies at once. It’s just a guess, but I’ll bet that bad customer data costs companies $trillions, especially if you throw in all the bad guesswork produced by unwelcome (and increasingly illegal) surveillance-based guesswork. That’s a lot of savings.

We haven’t got that tool yet because we’re accustomed to thinking that business problems can only be solved from the business side. And correcting bad KYC data is just one of many business problems that are best or only fixed from the customer side.

So let’s look at some more of those:

Subscriptions. The world is approaching peak subscription. One reason is that every seller prefers a steady income to one-time sales. Another is that nearly all subscription services are out to screw us. They are built to bait us into subscribing and to game us afterward, for example by assuming we won’t remember that fees go way up after an “introductory” period. Every company with a subscription model also has its own user interface, so we have no way to scale our power to subscribe, unsubscribe, or monitor the “deals” being offered to acquire or keep subscribers. Think about how much better relationships with business will get when one side isn’t always out to screw the other. (For more on this, see Time to unscrew subscriptions.)

Terms and conditions. It’s insane that we should “accept” as many different sets of terms and conditions as there are websites and services. These “agreements” aren’t, and offer no way for us to record, audit, or dispute them. Regulations have only made things worse. The only real solution is for them to agree to our terms. This is totally doable because our terms (unlike theirs) can be friendly helpful, and work at scale. The IEEE has a working group (which I am on) drafting P7012 Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms. And Customer Commons already has a term called #nostalking, which says “show me ads not based on tracking me.” That way sites can continue to make money with advertising while we keep our privacy.

Payments. For demand and supply to be truly balanced, and for customers to operate at full agency in an open marketplace (which the Internet was designed to support), customers should have their own pricing gun: a way to signal—and actually pay willing sellers—as much as they like, however, they like, for whatever they like, on their own terms. There is already a design for that, called Emancipay. Once implemented, it can result in markets that are far more active and inclusive than the seller-controlled markets we have today.

Intentcasting. Advertising is all guesswork, which involves massive waste. But what if customers could safely and securely advertise what they want, and only to qualified and ready sellers? This is called intentcasting, and to some degree, it already exists. Here is a list of intentcasting providers on the ProjectVRM Development Work list.

Shopping. Why can’t you have your own shopping cart on the Web—one that you take from store to store? (My wife first asked for one in 1995.) There is nothing to stop us from inventing one, other than the absent imagination of our feudal overlords. When we do have our own shopping carts, sellers are likely to enjoy more sales than they get with the current system of carts exclusive to sellers alone. These carts, like our wallets, our browsers, our email clients, and other instruments we use for engaging in the digital world, should be substitutable.

Internet of Things. What we have so far are the Apple of things, the Amazon of things, the Google of things, the Samsung of things, the Sonos of things, and so on. All are confined to separate, proprietary, and exclusive systems we don’t control. Things we own on the Internet should be our things. We should be able to control them, as independent operators, as we do with our computers and mobile devices.

Loyalty. All loyalty programs are coercive gimmicks with high operational and cognitive overhead for sellers and customers alike. True loyalty is also worth far more to companies than the coerced kind, and only customers are in a position to truly and fully express it. So we should have our own loyalty programs, to which companies are members, rather than the reverse. This is a vast greenfield of opportunity that will only open when it is approached from the customers’ side.

Privacy. We’ve had privacy tech in the physical world since the invention of clothing, shelter, locks, doors, shades, shutters, and other ways to limit what others can see or hear. We also have well-understood ways to signal what’s okay and what’s not. Online, however, all we have are mostly insincere and unenforced promises by others not to watch our naked selves, and not to report what they see to parties unknown. We can only fix this by recognizing that privacy is personal: it’s also about personal control and personal signaling of preferences and intentions. Developing privacy tech and sensible norms needs to start from those simple facts.

A dashboard for knowing and controlling our digital lives. The time has come for us to have complete knowledge and control over our finances, property, subscriptions, contacts, calendars, creative works, and everything else in our lives. Nothing inside Apple’s, Google’s, Microsoft, or any other giants’ castle comes close to doing that. It’s also not a new idea. We’ve been talking about it at ProjectVRM since it started in 2006, and I’ve been writing about it since the mid-’90s when the Net and the Web started to look real. For example, here. KuppingerCole has been writing and thinking about these things (calling them “life management platforms”) since not long after they gave ProjectVRM an award for its work on all this, in 2007. Solutions in this space have gone by many labels: personal data clouds, vaults, dashboards, cockpits, and lockers, to name a few. Many designs in recent years have focused on social data—the data Facebook, Google, TikTok, and others have about us, for example. But data matters less than agency: real control over our lives in a world that has gone digital.

Identity. Work is already happening here, mostly around what’s called self-sovereign identity, aka SSI. Look up SSI self sovereign identity on Google and you’ll get nearly a million results. With SSI you don’t show “an ID.” Instead, you present “verifiable credentials.” That means all your wallet says to the other party is that you have a ticket to the show, that you’re over eighteen, or that you hold a diploma. reveal no more than what another party needs to know. The main thing is that it gives you far more control over what you reveal about yourself and your stuff.

Health care. This is an especially difficult one to solve in the U.S., where health care is considered a privilege rather than a right, and the whole thing is a B2B insurance business. But there are worthy efforts going on here, such as HIE of One.

Many (or perhaps all) of those inventions will involve digital wallets, which I discussed in our last newsletter. All these solutions, and more, will be on the table at today’s VRM Day, and at IIW over the next three days of this week. Hope to see you at one or both of those.

Agree 100% and our business is named/being built on the premise that the true owners of data (all 8 billion of us + ~400 million businesses) must be empowered to own, earn from and do good with our data and hence the name Client Fabric Tech.